On Monday 2nd August we had our first indoor choir session since the 16th of March 2020. That is 504 long days since we sang together in a hall.

How did it feel? It definitely didn’t feel normal. It is quite different from our rehearsals before the pandemic.

This is a new phase. We are in a new venue, for a start. We have chairs and everyone sits or stands in the same place. We used to start off in a circle and do quite a lot of moving about in the first session, smiling and interacting with the other choir members. It’s harder to connect when everyone is facing the front and looking at the back of people’s heads.

I took everyone’s temperature as they arrived and we scanned or signed ourselves in. It was exciting but I think everyone felt a tinge of anxiety.

We asked everyone to do a lateral flow test that day – not asking for proof, just requesting it as a courtesy to the group. I loved how many people arrived brandishing either their actual test strip or a picture of it on their phone!

I’d been surprised by how few people signed up for the session. Back in May we had 20 people on the list. For Monday’s session we only had 14 volunteers, and not all of them came. One had a nightmare motorway journey and didn’t make it back in time, and as for the other two…

At 5pm I got a phone call from a choir member – one of a couple who were both looking forward to singing that evening, saying “I’ve just done the lateral flow test and it’s positive!” They didn’t have any of the classic Covid symptoms and were shocked by the result.

It made me very glad that I’d asked everyone to test. It also reinforced my feeling that there is a lot of Covid about. Almost everyone I talk to knows someone who either has the virus or is isolating.

The rate of Covid cases in Sheffield this week is 481.1 cases per 100,000. That’s significantly more than the rate for England, which is 283.7. The evidence supports my impression – there is a lot of it about. So I am going to carry on being cautious, welcoming people back gradually, and not until they feel ready. We are planning to sing outside again next week, and on the 23rd, and have one more indoor session on the 16th. It’s all fluid. There is no “new normal” unless the new normal is that we creep along cautiously, planning only a couple of weeks in advance.

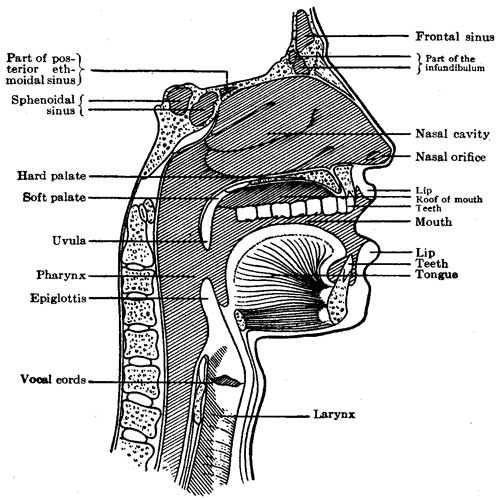

And the singing? Oh, the singing was glorious. The blend of voices, wrapped up in the lovely reverberation a good hall gives you, was beautiful. At times, if I shut my eyes, I would not have known how many individuals were singing, as the sound was so unified. It is quite different from singing in the garden, where even on a still evening the air whisks our voices away before they can mesh with each other.